Urban Exhibitions

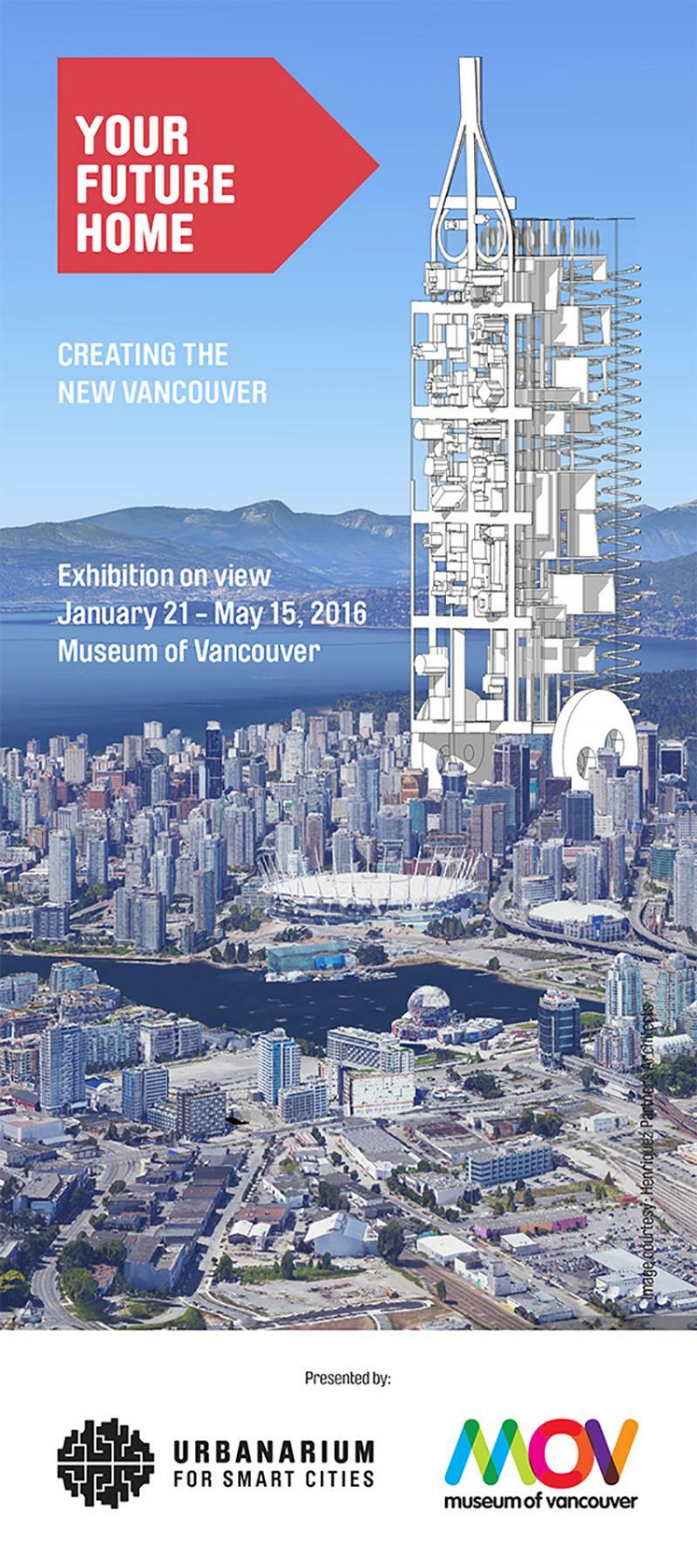

Your Future Home: Creating the New Vancouver

Future Scenarios

"Your Future Home" explored the hottest topics in Vancouver—housing, affordability, urban density, mobility, and public space—the show invited people to discover surprising facts about the city and imagine what Metro Vancouver might become. This major exhibition engaged visitors with the bold visual language and lingo of real estate advertising. In the "Future Scenarios" section of the show, talented Vancouver designers presented visions of how we might design the cityscapes of the future.

These visions spanned the full range of ideas from interpretive takes on current issues, thoughtful analysis of the results of current trends projected into the future, all the way through to provocative and radical ideas.

These imaginations shared a gallery with the "Case Studies", examples of big urban moves that shaped Vancouver in the past.

As always with the Urbanarium, our intent was to support citizens ofMetro Vancouver in imagining and working towards a better city.

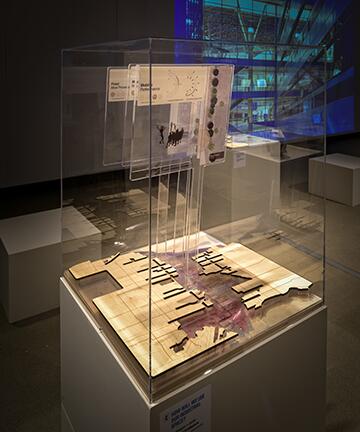

Residential Density

Traffic, noise, pollution, and the overshadowing of neighbouring properties are concerns voiced by opponents of urban density. The other side of the argument is that densification means a walkable city with the ability to bike or take public transit. The denser city is a more sustainable, vibrant place with better and more varied services, employment possibilities, cultural offerings, educational opportunities and recreational options This design explores densification, while taking to an extreme the love Vancouverites have for the view. We created the 2,500-foot-tall structure by placing upright a 15-block area of the city (bounded by Seymour, Howe, Pacific and Robson Streets), complete with existing buildings and bridge ramps. Behind this is a structural grid within which are suspended elements that house a variety of functions. A huge rooftop holds a sky-park that offers dramatic views. People can reach suspended sections via a series of overlapping bike ramps, the straight ones going up and the spiral ones going down. This wheeled structure is really a vehicle that envisions a dramatic shift in scale in relation to present-day Vancouver.

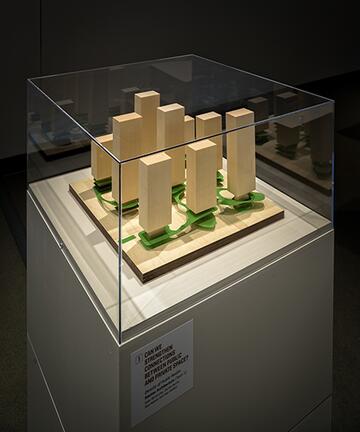

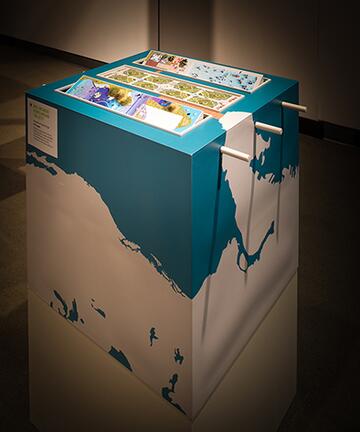

Our proposal is a visual exploration of the home within the context of Vancouver’s neighbourhoods. Future Densities reconsiders three common housing types in three scales as they relate to current zoning guidelines—and as they might relate to less restrictive future zoning requirements. Our proposal imagines how duplication and blending of familiar Vancouver housing might create high-density, livable neighbourhoods in the future.

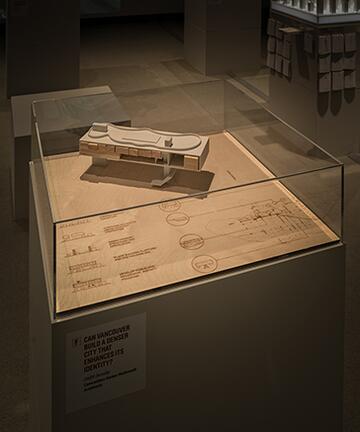

Vancouver aspires to be a sustainable, dynamic, and resourceful future city, internationally renowned for its distinctive natural character. In order to meet the Greenest City Action Plan 2050, while strengthening its sense of identity, Vancouver must embrace density and diversity in its building types and public spaces. This project reimagines and explores maximizing public-private resources in support of public space. It proposes expansion of public space into private territory—strengthening connection to the surrounding urban fabric through its fluid, accessible nature.

We imagine that, in the not so distant future, Vancouver will become so dense that the city grid no longer accommodates public space on the ground. In this congested future, developers will be mandated to provide public space within their buildings. In order to break the mould of a city comprised of seemingly identical towers, developers will be permitted only to market buildings by advertising their public space. The developers will compete for buyers by building unique and adventurous towers that breathe new life into the homogenous cityscape. We encourage you to draw over the provided diagrams. Add your take on how these public spaces might be used. Post your #publicamenityno1 on Instagram and Twitter to share your vision.

We know that density alone does not create healthy communities, but knowing what not to do is not a road map to what we should do. As Vancouver negotiates additional density it needs to break free from notions of ‘good urbanism’ that promote segregation, uniformity, obvious order and quiet. Like many before us we posit that in order to create rich urban textures we have to recognize that intricacies and diversity do not bring about chaos that needs to be overcome but instead give rise to complexity and highly developed forms of order that define neighbourhoods and promote communities. We need to overcome our fear of contagion, allow a rich mix of adjacencies and form in our developments, and provide pedestrian scale commerce on our streets in order to create meaningful opportunities for social interaction. Not to do so will mean the continued destruction of our neighbourhoods and our city.

Housing today is facing significant challenges. We live in a world that is changing at an unprecedented rate in terms of technology, migration, social life and global economic interdependencies, while global warming is presenting increasing pressure to rethink models of the past. Typical housing development is driven by short term profit thinking that has led to an affordability crisis, often creating ‘units’, not homes, that lack innovation, imagination, livability, sustainability and quality. In Vancouver, housing is typically either low-rise or high-rise living with little in between. In response, the Monad model has been conceived as a generative platform for mixed use, intermediate scale (4-15 storeys) developments making dense urban living desirable. This holistically integrated model offers high-quality livability, affordability based on actual needs and desires, long-term sustainability and energy efficiency, directly coexisting with spaces for layered social connections, public programs and places to work. Monad is adaptable to varying development site and needs for customization. This is achieved through systematic design integration, advanced technology, low energy design, mass timber structures and off-site prefabrication.

Onfill Housing assumes that increased density brings economic, social, and cultural benefits for communities and the city at large—while keeping successful residential and commercial communities intact. Regulatory reform would allow a more nimble approach to property ownership and increased responsiveness to Vancouver’s market pressures. This proposal requires an elaboration of Vancouver’s existing Density Bonus tool in order to allow owners the right to combine the sale of density and air rights and enable new development to bridge directly over existing buildings. The result is a series of medium density additions that maintain much of the physical fabric. The sale of density, an expanded customer base, and more predictable property values would benefit the city.

Public Space

Compared to urbanites in other major Canadian cities, Vancouverites work the fewest number of hours a week. If this trend continues, Vancouver will have the highest rate of uselessness across Canada. How will the city reshape to accommodate billions of annual person-hours of non-productive leisure time? We are pursuing this question by rethinking Vancouver's recreational talisman, Stanley Park. In our proposal, the sacrosanct natural habitat of the park is untouched. Meanwhile, the spaces designed for human occupation, such as the seawall and the trail system, are expanded to accommodate at least double the traffic. Division, multiplication, and bubbling maximize the capacity of the spaces. The bubble is the geometry that generates maximal surface area for a given volume. Bubbles rise to the surface, occur in the air, or are suspended in the matter of the site. The emerging tension between natural habitat and new volumetric leisure zones is the site of a battleground between the old and new urbanizing systems.

Downtown Vancouver lacks two things: public gathering spaces and engagement with the water. As one of the most densely populated cities in Canada, Vancouver is lacking in outdoor public space, however, creation of new outdoor public space is extremely challenging due to the high cost of land. Meanwhile, the non-industrial portions of the waterfront are contained within a continuous ribbon of seawall that propels citizens along the water’s edge rather than encouraging them to engage with it. The Coal Harbour Deck presents a dynamic strategy for the creation of a series of public spaces that reconnect people with the water. Our strategy proposes to provide ways for all citizens to make new connections while engaging in active and passive recreation. Harbour Deck is not a pool. It’s not a park or a pier either. It’s a new type of public space that activates Vancouver’s waterfront.

Water has always shaped Vancouver’s destiny. As our climate changes, sea level rise will be a transformative force. This gauge will help Vancouver’s thinkers, builders, and shapers visualize the consequences. Each mark, which indicates one metre of sea level rise, represents a future scenario for a city that must mitigate, adapt, protect, and retreat.

Vancouver’s Smallest Public Park is deployed around Vancouver in otherwise neglected public spaces such as traffic circles, construction hoarding, medians, slip lanes, under bridges, and parking lots. The park encourages performative situations such as smoking, dog walking, and escaping the rain. The park is equipped with the basic amenities of public space: seating/leaning spaces, shade, turf and plantings, along with opportunities for self-expression.

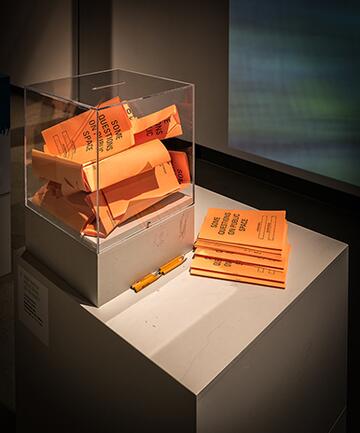

What is public space? What potential does it hold in Vancouver? What kind of spaces do we want to create in the city? Artist collective Broken City Lab and the Contemporary Art Gallery (CAG) encourage your participation in discussions about public space. We invite you to respond to questions about the intersection of public space, art, and civic life. These questions range from semi-statistical to poetic fill-in-the-blanks. Your answers will help generate a loose mapping of Vancouverites’ emotional connection to ideas about home, urban development, and public space. The CAG will scan responses and post on Instagram: @CAGVancouver, Facebook: Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver and Twitter: @CAGVancouver.

Vancouver has long-lamented its lack of a central, unifying downtown square. It is critiqued for its enchantment with its perimeter, its beaches, and views beyond. But Vancouver is a coastal metropolis, embedded in lush forests, mountains, and ocean. These natural elements are central to everyday experience. The shoreline, bays, and water have always been social spaces, accommodating grand ceremony and everyday gatherings. BargePark proposes a mobile system of programmed parks. Collectively able to form a large multifunctional civic park and to disband to diverse locations, a series of unique barges would embrace Vancouver’s aquatic obsession, and raise questions about land use, access, and the relationship between city and nature. The barges would contain pastoral parks and floating forests, botanical gardens and community kelp farms, kayak-in theatre and recreational fields, floating swimming pools and sculpture gardens, campgrounds and concert grounds, amusement parks and playgrounds.

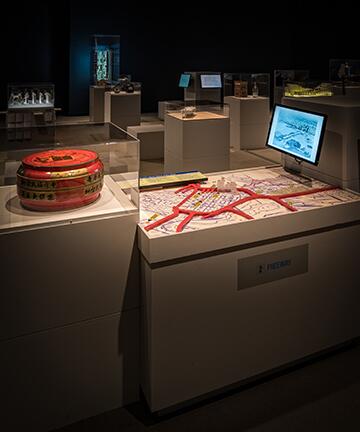

Transportation

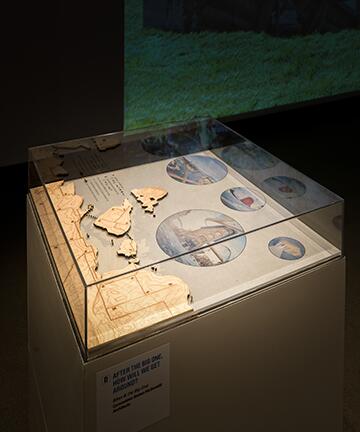

When The Big One comes, will you be ready? Of course, you are at least a little ready, holding the understanding that at some point, the ground beneath your feet will shift violently and change the region forever. You know the basics: water for three days; hand-cranked radios and flashlights; pick a family meeting place. But when the dust settles, how will you get around in the days and weeks following? Your car may be trapped underground. You own a smart car, not a 4x4. There's not enough gas. Bikes & the Big One addresses this question by augmenting the region's existing bicycle infrastructure to enable the movement of people and small-scale goods. Situated above the anticipated high-water flood line that results from a significant earthquake, this soft-infrastructure would allow the circumnavigation of the city and provide access to otherwise unreachable neighbourhoods like Vancouver's West End. Coupled with harder infrastructure that would serve to bridge new waterways and provide access to basic utilities like power and water treatment, the network could provide a much-needed temporary lifeline for neighbourhoods and the region at large.

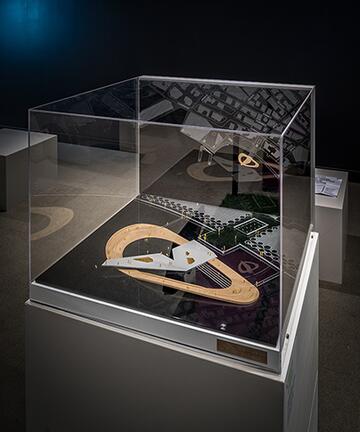

Vancouver’s orphaned spaces hold the potential to redefine the urban environment by facilitating the testing of mobile and temporary architectures. A pertinent example of underutilized space in Vancouver is the 45-acre Arbutus Corridor, an intact 15km rail line that runs from False Creek to the Fraser River. Although the Canadian Pacific Railroad ran service on this line until 2001, usage has been intermittent for over twenty years. Economic and emotional investment in the site has been limited, due to uncertainty about the line’s future, which has resulted from the legal battle over use of the land. We have been exploring the systematic reimagining and reprogramming of this ‘lost’ infrastructural space since the mid-1990s. Our model turns the limitations imposed by a recent Supreme Court ruling, which zones the line primarily for transportation, into opportunities for the seasonal deployment of demographically diverse uses. Here, we offer a laboratory for the investigation of alternative methods for the creation of urban space. Our model highlights a series of interventions along the rail line that are programmed based on contextual mapping overlays of the immediate surroundings. Each intervention is coded based on seasonal and hourly occupation cycles as well as the installation type (mobile or fixed) used for that intervention.

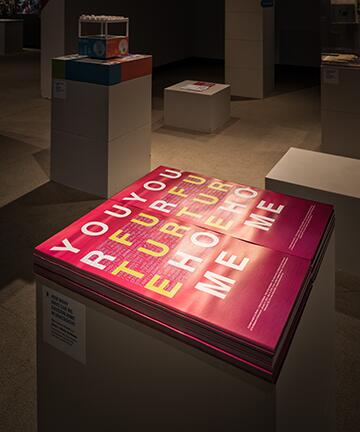

We hope that this exhibition will lead to more public and private conversations about Vancouver and will inspire you to consider how we can all participate, individually and collectively, in the ongoing construction of our home. Please take a poster home with you. (The same poster sits on both piles—with opposing sides shown).

Our vision for Vancouver reimagines how we live and move around our city. We believe it is possible to travel easily and enjoyably through an environment that is safe for our children, supports local economies, and promotes social justice. Transportation accounts for one quarter of Canada’s Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions and more than one third of the City of Vancouver’s GHG emissions. We propose a strategy that eliminates the need for private automobiles and repurposes our cities to allow for full and invigorating public life. Our work is based on the following principles: Social Equity Access to high quality, affordable transportation for all Access to green space, schools, jobs and daily needs for all Sustainability Prioritize low impact transportation Provide a functioning network of ecological services Human Habitat Allow for a broad range of outdoor activities in public space Distribute density and employment in a holistic way that supports livability

How we travel from place to place determines the quality of our lives and the nature of our interactions with others. Vancouver’s population of over 600,000 has over 600,000 unique daily destinations in the region, often navigated via shared modes of transportation. Each mode has its distinctive landscapes, perspectives, and implications. MOVE spotlights the trajectories of three Vancouverites as it highlights that everyday transportation options are—and will continue to be—essential to our future lives and the future of Vancouver. We created this documentary, reinterpreted for Your Future Home, as an undergraduate project with Kate Hennessy at Simon Fraser University, in collaboration with CityStudio and the City of Vancouver. Thanks to Rachel Ho, Shem Navalta, Dean Mitchell, Purebread, Old Faithful Shop, Opus, Jeanie Morton, and Karla Kloepper.

Housing Affordability

c̓əsnaʔəm_vancouver_triangle invokes architecture's capacity to embrace the literal and the abstract, the recent past, and the distant future. Speculations about the future spring from our past and present, replete with myths, memories, and popular misconceptions. Appropriate forms of housing continue to occupy our imaginations; affordability and homelessness are daily topics of debate. What is home, here, c̓əsnaʔəm_vancouver, in the 21st century? Forest, clearing, location, tent, lean-to, teepee, shed, lodge, house, cabin, cottage, camp, playhouse, park, playground, village, settlement, tower, special, dwelling, walk-up, hotel, pad, room, suite, quarters, unit, yard, boathouse, vessel, jail, cell, dorm, abode, laneway, tenement, street, flophouse, mansion, estate, property, condo, slum, hospice, digs, hostel, apartment, hearth, domicile, habitat, niche, home… The solutions are neither black nor white. The answers lie in between.

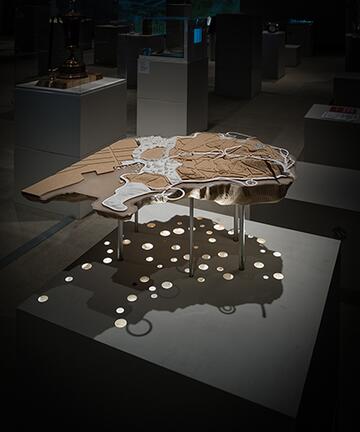

In the not too distant future, governments, policy makers, city planners, and decision makers will depend on the citizen to determine the needs of the city. A truly "Smart City" will rely on form and accessible technologies to connect communities. The city and its skyline will become as adaptable and interactive as a game of Tetris. Waves of incoming populations and development will fall like Tetris blocks on Vancouver's city grid. A player may want to pack in the pieces as quickly and logically as possible. As the rate of city growth increases, arranging city blocks becomes harder. Divorced from context, some moves may look peculiar, but planners and local officials keep "the game" going. In Tetris, this means stacking blocks higher and less efficiently than one would like. By leveraging participation, decisions become less a matter of haphazard placement than a conversation about encouraging smart and sustainable growth. Our physical model represents a comparison of present day data: the existing city skyline and its relationship to population density and rental costs. The Challenge: Have a say in how you envision the city and play a game of Tetris! Manipulate Vancouver's future on the iPad by arranging your preferred population, rental, and building blocks in the existing city framework.

Can you afford to be here? Reflections on affordability.

Affordability is intimately connected to the urban grid of Vancouver. Within the grid there is a hierarchy of public and private spaces, ranked according to topography, land use, and geographic features. Similar in spirit to the exhibition you are walking through, the work in front of you proposes a return to a non-hierarchical GRID—a pattern that fosters access, democracy, equality, and affordability. This alternative GRID, overlaid on the existing city, is both surface and structure; predictable and indeterminate; prescriptive and ambiguous. Citizens of this alternative order will, therefore, have to learn to exploit its pattern, inventing new ways to inhabit it, experimenting with new forms and adjacencies—and in doing so, create a new spatial and social order.

The healthcare system does a pretty good job of dealing with 90% of us … we go to our family doctor or a walk-in clinic with an ear infection, we show our CareCard, get diagnosed, receive a prescription which we promptly get filled and take according to the directions … and we’re done. For 10% of us things aren’t so simple. Due to issues associated with youth, addiction, homelessness, poverty, mental health, no family doctor, no CareCard, or no fixed address … access to healthcare can be very difficult. DOC is envisioned as a 24/7 no-threshold gateway to the healthcare and associated support systems. DOC doesn’t discriminate … all are welcomed at these DELIGHTFUL OUTREACH CENTRES dotted throughout Metro Vancouver, where access is easy, friendly and up-beat. DOC is a network, a service, a place and a brand.

Case Studies

The case studies focus on changes to Vancouver and the region that were influenced during their planning and development by the interventions of citizen activists and innovative professionals. The history of city building, and game-changing projects, is intended to be featured by the Urbanarium – in temporary exhibits, the website, and in our hoped-for permanent home.

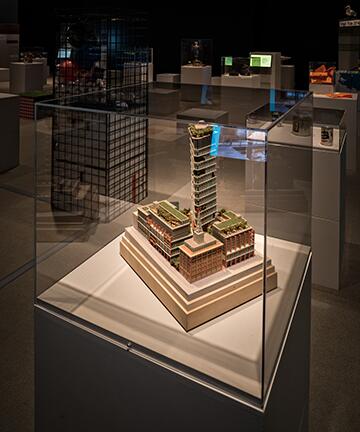

25 years ago, an unusual alliance—an insurance company, a university, and the City of Surrey—transformed a worn-out mall in a poor neighbourhood into the start of a thriving downtown. This is a story of innovative ideas coming from collaboration among unlikely sources rather than the neighbourhood advocacy featured in other case histories. At the time, Whalley had few local activists. Architect Bing Thom had a breakthrough idea. The Insurance Corporation of British Columbia was looking for real estate investment opportunities and bought an aging shopping centre for repurposing. The City donated land in the designated city centre and the Province agreed to locate the new university there. Mayor Bob Bose supported the idea and advocated for the City of Surrey’s interests. The key design idea was ripping the roof off the existing shopping centre and placing the university classrooms in a tower above it.

Community advocacy by Strathcona residents, supported by the intervention of young activists, stopped the construction of a freeway through Strathcona and Chinatown and along the downtown waterfront. Strathcona and Chinatown today are significant Vancouver neighbourhoods. But in the 1950s and 60s, they narrowly avoided the wrecking ball of “progress.” Stopping the freeway was a major turning point in Vancouver history. In the 1950s and 60s, Vancouver’s most powerful interests, including politicians, businesspeople, city planners, and architects, were in favour of a new highway system that would converge in the city centre. Led by Bessie Lee and the Chan family (Mary Lee, Walter and Shirley), the Strathcona Property Owners & Tenants Association (SPOTA) fought back, quickly gaining the support of young social planner and future city councillor Darlene Marzari. Together, they organized protests and lobbied local politicians and administrators. With the support of her boss, and at great risk to both of their jobs, Marzari, with Shirley Chan, organized a tour of Strathcona for visiting Federal Minister of Housing Paul Hellyer. Following the tour, the minister froze federal support for the urban renewal project. Once Strathcona had been saved, Chinatown was easier to rescue.

The creative involvement of the community in the rebuilding of Arbutus Lands was an important moment in Vancouver’s planning history. The result was a welcoming, and compatible, neighbourhood able to include a much larger number of people who would call it their home. The decision by Molson’s/Carling O’Keefe to close their brewery in Kitsilano and develop it for multiple family housing generated controversy when proposed in the late 1980s. The initial development plans imagined a series of point towers similar to ones being built around downtown at the time. The City of Vancouver initiated a Local Area Plan program and invited Kitsilano residents and business owners to contribute their ideas for the future of the brewery site. The city government committed the necessary staff resources to effectively engage with the community. Residents held open houses and prepared their own plans, policies and proposals. A consensus urban design plan was produced by the community. The community supported a substantive increase in density by using building forms that fit better with the neighbourhood.

A group of engineers invested in a system that distributes steam energy from a central plant, thereby eliminating the need to install boilers in every major building downtown. As downtown Vancouver became a major commercial centre in the 1960s, local engineer Jim Barnes and a group of his peers proposed building a district energy system. The goal was a more efficient energy delivery system for the compact downtown. The plant opened in 1968 on Beatty Street. The plant currently provides heat to more than 210 buildings. Were it not for the central heat plant, there would be hundreds more smokestacks on the Vancouver skyline, all under various ownerships and states of maintenance. The system serves more than 4,000,000 metres (45,000,000 square feet) of space downtown through a 14-kilometre (9-mile) network of underground pipes.

Hastings Park began in the 1880s as one of Vancouver’s first parks, with forested glades and a picturesque stream. By the early 1900s, the park became the site of an annual exhibition. Buildings, pavement and a racetrack were built. Over the next eighty years, so many exhibition facilities were built that little of the original green park remained. In the 1990s, concerned local citizens demanded that Hastings Park, paved from edge to edge, be restored as a green park. Using original legal documents, citizens made the case that Hastings Park was meant to be a park for the use and enjoyment of city residents. With intensive community participation, a master plan was prepared and has since been updated. Throughout the process, plans have been inspired by the idea of daylighting the historic stream and returning salmon habitat to the site.

Granville Island was a derelict industrial area when the federal government and a group of local architects and planners saw an opportunity to create a new cultural and community center for Vancouver. Granville Island started as a sandbar that was enlarged to its current size in 1915 with fill dredged from False Creek. By 1923, it was covered with corrugated metal industrial buildings. Industrial uses dominated for the next fifty years. By the mid-1960s, the industry was leaving the island. Much of it was neglected. Ron Basford, a long-time Cabinet minister from BC in the Liberal government of Pierre Trudeau, advocated for the redevelopment of Granville Island when he was the Minister of State for Urban Affairs. In 1972, he announced funding for the project. With the innovative design and adaptive use of industrial heritage, the Island has been a top destination for tourists as well as a place enjoyed by locals.

Woodward’s was developed as an inclusive mixed-use, urban renewal project on the site of a beloved, historic department store, in Canada’s poorest postal code, Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Woodward’s Department Store was the anchor of a vibrant shopping district on Hastings Street since the beginning of the 20th century. After the store closed in 1993, the building sat empty for a decade in a neighbourhood with economic and social challenges. Ideas were floated, including market housing. In response to advocacy for social housing, the Province bought the site in 2001. In 2002, activists in the Downtown Eastside occupied the sidewalks around the building for 92 days, galvanizing public opinion. Activists protested against the gentrification of the area and expressed demands for more social housing. They gained hundreds of supporters, some of whom joined the movement. The City of Vancouver purchased the site from the provincial government in 2003 and began an extensive public consultation process that included community visioning workshops. City Councillor Jim Green took a leadership role, mediating among varying interests. The City ran a competition for an inclusive design that resulted in the varied mix of housing, heritage, and cultural institutions there today.

The concerted efforts of citizen and heritage activists led to the preservation of Mole Hill, a residential block in Vancouver’s West End and its transformation into social housing. With a history dating to 1888, this neighbourhood of 36 houses and one apartment building represents a cross-section of early Vancouver architecture and streetscape. Beginning in the 1950s and continuing until 1984, the city government bought properties in the area. The city government demolished a block of houses similar to Mole Hill in order to create Nelson Park, while renting the Mole Hill houses. In the 1990s the Park Board proposed an expansion of Nelson Park to serve the rapidly densifying West End. A part of the block was identified for a new apartment building, to defray a loan against the property. Seven years of community advocacy for keeping the housing convinced the city to change its plans for park space and new development. In October 1999, Council officially started the restoration process.

Location: MOV

49.276345568447, -123.14444275

,

Credits

The Vancouver Urbanarium Society and Museum of Vancouver present

Your Future Home: Creating the New Vancouver

Museum of Vancouver

Lead Curator: Gregory Dreicer

Curatorial Associate: Jillian Povarchook

Curatorial team: Viviane Gosselin, Jane Lougheed, Wendy Nichols, Alan Kollins

Marketing: Myles Constable

Fabrication and installation: Klaus Koa and Heather Turnbull with Justine Rego, Evan Follweiter, and Nicholas Farrell

Program development: Mitra Mansour

Data Curator: Andy Yan/Bing Thom Architects and Simon Fraser University City Program

Graphic design: Cathryn Bingham, AldrichPears

Exhibition design: Office of McFarlane Biggar Architects + Designers

Design of family guide and related graphics: Mia Hansen

Chinese media representative: Joyce Yang

Media sponsors: CBC Vancouver and Vancouver is Awesome

Urbanarium Curatorial Team

Overall coordination: Scot Hein

Case Studies: Marta Farevaag

Future Scenarios: Bruce Haden

Vancouver animation coordination: Bo Helliwell

Communications: Ian Grais/Rethink

Panorama and animation content: Sam M. Khani

Project management and video editing: Elena Chernyshov

Mandarin translation: Minnie Chan

App development: Babak Manavi and Minnie Chan

The Urbanarium and Museum of Vancouver would like to thank the contributors of the future scenarios.

Broken City Lab / Contemporary Art Gallery

BTAworks

Campos Studio

Carscadden Stokes McDonald Architects

Clayton Blackman, Colin Harper, Shane Oleksiuk

DIALOG

Erick Villagomez

FubaLabo Design

Hapa Collaborative

HCMA Architecture + Design

Henriquez Partners Architects

Kyle Ball, Justine Crawford, Dorcas Yeung

LIMINAL

LWPAC

Measured Architecture

Perkins + Will

PFS Studio

SHAPE

Simcic + Uhrich Architects

Stantec Architecture

Stephanie Robb Architect

The Urbanarium and Museum of Vancouver would like to thank the individuals for their participation in the development of Your Future Home.

Justin Barski, Jane Bateman, David Beers, Mahbod Biazi, Craig Birston, Chanel Blouin, Gillian Brennan, Mark Busse, Karen Campbell, Patrick Y. Foong Chang, Thomas Daley, Frank Ducote, Carlos Fang, Megan Faulkner, Michael Flanigan, Steph Hurl, Neal LaMontagne, Derek Lee, Babak Manavi, Matthew McCauley, R.J. McCulloch, Jessika MacDonald, Sean McEwen, Darlene Marzari, Sarah Oxland, Doug Patterson, Blair Petrie, Chris Phillips, Nic Paolella, Omer Rashman, Mitchell Reardon, Andrea Smith, Erick Villagomez, Tate White, and Matthew Woodruff.

Your Future Home was made possible by generous contributions from:

AldrichPears Associates

Office of McFarland Biggar Architects + Designers

Bing Thom Architects and Simon Fraser University City Program

GeoSim Systems

Marcon Developments

Reliance Properties

John Atkin and Andy Coupland, changingvancouver.wordpress.com

Henriquez Partners Architects

Rethink

Vancouver home photographs: Office of McFarlane Biggar Architects + Designers

Vancouver model: James Bligh

Choose YOUR Vancouver photographs courtesy of Vancouver Sun; except BC Bike Race 2015, photo: Dave Silver

Vancouver: Then and Now contemporary photographs courtesy of Andy Coupland;

historic photographs courtesy of City of Vancouver Archives and Vancouver Public Library.

Virtual Vancouver 3D city model animation provided courtesy of GeoSim Systems.

Aerial photographs of Vancouver: Waite Air Photos

Digital retouching of aerial photos: The Lab—Professional Image Works

Historical artefacts: Museum of Vancouver

The Urbanarium and Museum of Vancouver are grateful for the support of Rositch Hemphill Architects, Marcon Investments Ltd., Wesgroup Properties LP, Macdonald Development Corporation, Glotman Simpson, Richard Henriquez, Henriquez Partners Architects, Rethink, Adera Development Corporation, BTY Consulting Group, Brooks Pooni Associates, PFS Studio, Bruce Haden, Andrew Gruft, Leslie Van Duzer, and Marta Farevaag.

Special thanks to the Museum of Vancouver’s institutional supporters:

City of Vancouver, BC Arts Council, and the Province of British Columbia.