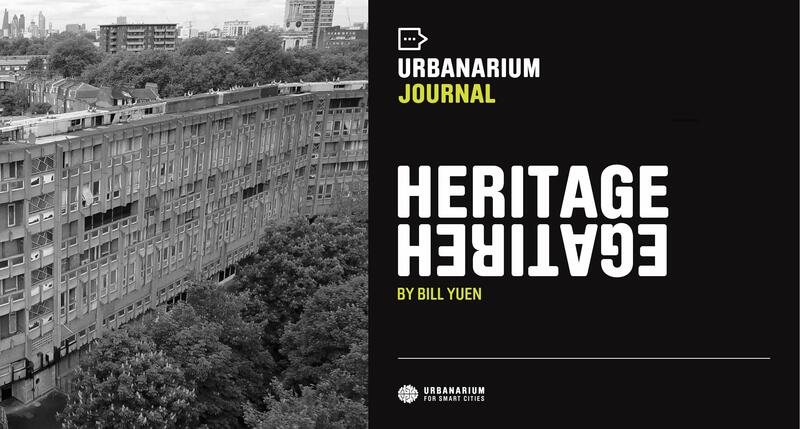

On November 11, 2022, ADFF screened Robin Hood Gardens in Vancouver. The screening was followed by a short Urbanarium panel discussion about the film. This journal entry is a written version of the comments made by Bill Yuen, one of the panelists, from the local non-profit Heritage Vancouver. It is a reflection on social history, place identity and meaning and how we might think differently about heritage.

In my opinion, Robin Hood Gardens is one of the best examples I have come across that exemplifies how complicated, fascinating, and impossible heritage is. Although I am writing from Vancouver and not London, the case around Robin Hood Gardens is quite applicable to Vancouver issues with contested identities of place -a major topic of heritage nowadays- and the housing crisis. This written reflection is rooted in Liza Fior’s comments in the film on how the campaign to save the building was led by architects instead of residents. Had it been the latter, she suggested, the building may have been saved. Her comments reminded me of someone lamenting at a local heritage event that a building might be saved for a reason other than the prominence of the architecture. Which prompts this question:

If Robin Hood Gardens had been saved, would it matter to you for what reason it had been?

At the time in 2017, the purchase of a segment of the building by the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) to add to its collection as well as the subsequent exhibition in the Venice Biennale generated some controversy. The museum was accused of -whether correctly or incorrectly- artwashing, whitewashing gentrification, displacement, and for fetishsizing the object without giving proper attention to the real people who have been affected, such as the tenants. Both the museum and Historic England were criticized for not working to save the building as housing for the working class or those with low incomes.

In the film, it was mentioned that the organization Historic England, which had the power to list and therefore protect the building from demolition, turned down the application for listing. According to the decision, Historic England essentially considered the building architecturally flawed and the name value of the Smithsons not sufficient enough to compensate for these failures in order to arrive at a decision to list the building.

A more postmodern idea of heritage involves fracture and multiplicity rather than the traditional one-single-narrative of a place usually determined by a single group. With Robin Hood Gardens, one perspective clearly exists on the level of a magnificent building by prominent architects. Richard Rogers and Simon Smithson wrote in an open letter appealing for the building’s preservation:

"The buildings are of outstanding architectural quality and significant historic interest, and public appreciation and understanding of the value of Modernist architecture has grown over the past five years, making the case for listing stronger than ever,"

On a different level, there are those who do not see the building as architecture or a creation of the Smithsons, regardless of its pedigree (they may not even know who they were). Because it was council housing, it has come to represent the housing crisis and financialization of housing for many people. The Thatcher government used as rationalization for the right to buy scheme the poor living conditions in council housing like at Robin Hood Gardens. In this view, Robin Hood Gardens is associated with the housing crisis, and the right to a home regardless of financial means.

To put the controversy around housing surrounding the exhibition in perspective, it is important to note that the inquiry into the fire at the Grenfell Tower was happening during the time of the Venice Biennale. The campaign to save the Elephant and Castle in Southwark was also happening during this time. The Elephant and Castle is a major regeneration scheme taking place in an area that has come to be an important affordable area for the Latin American and Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities in London (incidentally, the Elephant and Castle Shopping Centre, important to the migrant community as independent and affordable retail space, was also rejected for listed status by Historic England). The site of the Brutalist Heygate Estate -with over 1000 council homes- which was demolished from 2011 to 2014 to make way for over 3000 housing units is part of this regeneration area. The loss of social housing was very much in focus in 2017 and 2018; media outlets put out stories with headlines such as “Redeveloped with the promise of new social housing, the Heygate Estate's units have been entirely sold off to foreign investors”.

It is widely known that heritage is heavily influenced by architecture. Architecture is the basis of the preservation movement which in a contemporary paradigm of heritage can be viewed as one of a number of ways heritage is expressed (traditionally, the Western practice of heritage was mainly concerned with architectural preservation). You can see architecture’s influence (along with age) in Historic England’s rationale for rejecting the bid for listed status for Robin Hood Gardens:

In recommending a building for listing, particularly one so recently built, we need to consider whether it stands up as one of the best examples of its type. We don’t think that Robin Hood Gardens does. It was not innovative in its design – by the time the building was completed in 1972 the ‘streets-in-the-air’ approach was at least 20 years old. The building has some interesting qualities… but the architecture is bleak in many areas… and the status of Alison and Peter Smithson alone cannot override these drawbacks.

This evaluation method, largely aestheticizing the artifact, is also similar here in Vancouver. For example, the heritage of the Little Mountain Housing site in the Riley Park neighbourhood is largely evaluated based on the modernist design and the architects Thompson Berwick and Pratt. But Little Mountain has other heritage. It is also significant for being a site of the first public housing project in the province of British Columbia initiated by the federal and provincial governments that was later sold to a private developer and demolished, displacing close to 200 households; except for one replacement building, it is still sitting empty 13 years later.

In response to the criticism directed at the V&A, one of the justifications given for the purchase and exhibit in Venice is that the public will be aware of and continually discuss the predicament of housing when they see this portion of the building. Given the competing versions of what different people associate Robin Hood Gardens with and the social context at the time of the V&A purchase and Venice Biennale, I return to the opening question:

If Robin Hood Gardens had been saved, would it matter to you for what reason it had been?